There are those who believe that money writers lead perfect financial lives. Ha! Would that it were so. When we get together, we often share stories about the dumb things we’ve done. Today, my friends, I want to tell you about an instance in which I failed to follow my own advice, an example of how not to get rich slowly.

For several years now, one of my indulgences has been season tickets to the Portland Timbers, my home-town’s professional soccer team. I’ve been a Timbers fan since I was six years old. I used to listen to their exploits on the radio during the 1970s. I can still sing “Green is the Color” from memory:

When the new Portland Timbers joined Major League Soccer in 2011, I jumped at the chance to buy season tickets. (Here’s video I took from the Timbers’ first MLS game.) After Kim and I decided to embark on our RV adventure across the U.S., I thought I’d have to give up my seats. I was sad. But then my friend Joe made a great suggestion: “Why don’t you sell them to me for the season?” A win-win, right? Well, sort of…

What NOT to Do

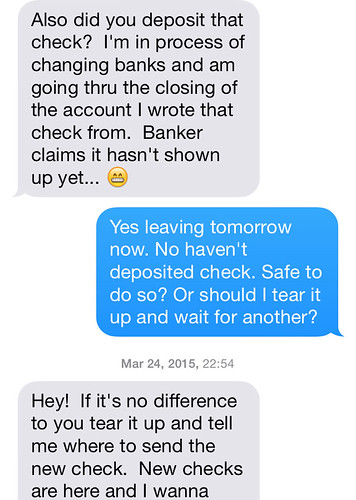

Joe paid me for half the season when I renewed the tickets in the autumn of 2014. Before Kim and I left on our RV trip in March 2015, he gave me an $800 check for the remaining balance. Then, on the night before we left Portland he sent me a text: “I’m in the process of changing banks…If it’s no difference to you tear it up and tell where to send a new check.”

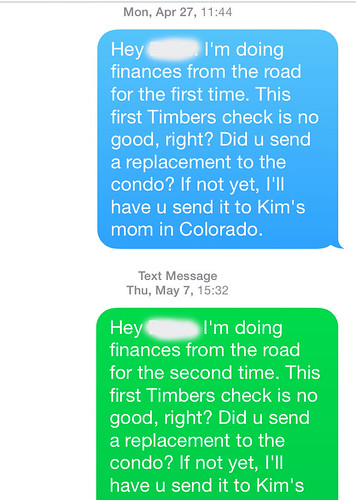

I replied with my home address (which Joe already had) but didn’t hear back. I sent another text in April but got no reply. In May, we connected. Joe agreed to send the check to Colorado, where we’d pick it up while visiting Kim’s mom. It took me a while to reply with the address, but when I did nothing happened. No big deal. I’m an easy-going guy. I figured we’d just connect elsewhere on the road.

In September 2015, Joe and I finally connected again. He told me had a check sitting on his desk, ready to mail. I suggested he send the money by Paypal and gave him my contact info. Nothing happened. I pinged him again the next week. Nothing. The week after that, still nothing. When we finally connected again in late October, Joe had a sob story for not paying but promised to send the money right away.

The holidays came, and I forgot about the $800. But Kim didn’t. The debt gnawed at her more than it did me. “I can’t believe Joe hasn’t paid you,” she said. I shrugged.

In late February 2016, Kim sent Joe a text asking if he was ever going to pay. This made Joe cranky. He texted me and asked what was up. “I did pay you,” he said. “I sent the money by Paypal.” I checked my Paypal account. I had never received payment from him.

I sent Joe an email outlining the entire sequence of events. I tried to keep my tone calm and reasonable (because truly, I wasn’t angry) but I wanted him to see things from my perspective: He’d had a year to pay me for the tickets, but hadn’t managed to do so.

Joe wrote back immediately:

This is insanely frustrating. First of all JD. I think you’re a great dude, and I appreciate what you were trying to do here for both of our benefit. You clearly have a good knack for letting things slip thru the cracks.

While Joe wasn’t wrong — I do have a knack for letting things slip through the cracks — I found his logic puzzling. His failure to pay was a result of my slow replies? I wrote back:

It’s not my responsibility to manage this situation. I haven’t let anything fall through the cracks. You are the one who owes the money. As such, you are responsible for paying in a timely manner. You, as the debtor, are responsible for repaying the debt without the lender having to hound you.

I’ve given you my mailing addresses (and Paypal addresses) repeatedly yet never received payment. I’ve also followed up several times without any sort of reply from you. It’s true that I haven’t always been prompt in my own replies — I own this — but that lack of promptness in no way changes the fact that you’ve had the info you need to pay since March 30th of last year.

I don’t want to argue over who should have been better at communication. I love my big buddy Joe and don’t want you to feel like I’m dogging you. As I said before, I’m not angry. But I think we can both agree that we need to get this fixed.

Joe never replied to my email. It’s now February 2018, two years since I last heard from my friend, and I suspect I’ll ever get paid. One thing’s for certain, though: At this point, our friendship has disappeared, and that’s too bad. (I, for one, would be happy to patch things up. I like Joe!)

I’m not sharing this story to demonize Joe. Obviously, I think he’s ultimately responsible for this situation, but I acknowledge that on my end, I’ve been a poor communicator. Plus, if I had deposited his check when he gave it to me before the RV trip, none of this would have happened.

No, my aim here is to provide a real-life example of what can happen when we lend (or borrow) money from family and friends. There are smart ways to do this and there are dumb ways. Joe and I chose a dumb way. (And yes, I realize this didn’t start out as a loan, but that’s effectively what it is now.)

Let’s look at the right way to lend money to family and friends.

The Right Way to Lend Money to Family and Friends

When a friend or a family member asks to borrow money, your first inclination is probably to help. But many people have learned the hard way that friendships and finances make a poor mix. My interaction with Joe is a typical example.

Not all loans between family and friends end in disaster, of course. In fact, although I’ve never been able to find stats on the subject, I’d be willing to wager that most loans go smoothly. But the potential for trouble is so great that you should think twice before lending (or borrowing) money. How would it affect your finances — and your friendship? Even when things do go right, the situation can get awkward.

For instance, in 2011 I made a large loan to a friend for a business project. That project fizzled. For the past seven years, my friend has always made his payments on time, but he’s had a tough time paying down the principal. For most of the life of the loan, he’s made interest-only payments. (This is a good deal for me, but not for him.) My friend I have maintained a good relationship, but it’d be even better without the money situation looming over our heads.

You can save yourself a lot of grief by knowing in advance what you’ll do when somebody asks to borrow from you.

Some people decide they’ll never make personal loans. If they’re asked, they say something like, “Sorry, but it’s my policy never to lend money to people I know.” If you think this is too harsh, you can offer to help in some other way. Most of the time, you’re probably better off saying “no” than putting yourself in a position where you have to hound a friend for money, as I’ve had to do with Joe.

Despite these warnings, some of you will be tempted to lend money. If you do, follow these rules. You’ll be glad you did.

- Discuss other options. Are there other ways to help? Sometimes people think money is the only way to deal with problems when there are actually other ways to offer assistance. Figure out what the root problem is and see if there are other ways to help solve it without donating dollars.

- Lend only the amount you can afford to lose. You may never see the money again, so don’t put your own financial well-being on the line for your cousin Bob. Make sure your own situation is solid before you lend money. (In my case, losing the $800 Joe owes me does hurt, but it doesn’t change my life trajectory.)

- Be clear about your expectations. Draw up a payment plan. You can use the online calculator at Bankrate.com to create a loan schedule. And discuss what will happen if something goes wrong.

- Get it in writing. At LawDepot.com, you can fill out a web form, and for $15 you get a complete promissory note. There’s also a free sample template at ExpertLaw.com. When I loaned money to my friend for his business project, we had an actual written contract.

- Deal with problems right away. You may feel you’re being kind by not sending a reminder that the payment is 30 days past due, but you’re just setting yourself up for trouble. Let the borrower know you’re keeping track. This is where I failed with Joe; I didn’t like reminding him to pay, so I went radio silent for several months thinking he’d simply man up. He didn’t.

Here’s another idea: If you can afford it (and if it seems appropriate), consider giving the money instead. That way there’s no ickiness on either side. If you get paid back, great; if not, you can feel good about helping out a friend in need. And remember: It’s always okay to politely refuse.

After my disaster with Joe, for instance, I decided to do something different with my Timbers tickets during the second year I was on the road. I simply gave them to Kris, my ex-wife. I know she loves going to the games just as much as I do. “Do you mind if I share these?” she asked. She ended up distributing them to our mutual friends. I lost out on the cost of the tickets in 2016, but I got to save my seats, I avoided hassling anyone for money, and my friends got to enjoy the MLS-champion Timbers in action!

One last thing: At some point, you may be the one borrowing money from a friend or family member. You should do this only if you can’t boost your income or tap an emergency fund. When you borrow, explain exactly why you need the money, put the deal in writing, and then stick to your word. Be proactive.

Keeping your word is the most important part. That means repaying the loan as promised — or sooner, if possible. Take this as seriously as you would any other financial obligation; in fact, take it more seriously. If you don’t pay the bank back, you’ll damage your credit score. But if you don’t pay back a friend, you’ll damage that friendship and your reputation. You don’t want to end up like me and Joe…

The post The right way (and the wrong way) to lend money to family and friends appeared first on Get Rich Slowly.

Via Finance http://www.rssmix.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment